Ned is just a helpful heuristic here, not an example of racist oppression.

In my previous post, I offered an annotated bibliography to help people interested in institutionalized forms of oppression and domination get started in understanding how those things work. In this post, I offer some framing and introductory material: what does it mean to accuse someone of being, say, racist or sexist? What is the force of that kind of accusation?

It is not about your intentions

The categories of “sexism,” “racism,” “heterosexism,” “classism,” “cissexism,” and the like are not best thought of as categories that pick out the intentions of the agents in question. That is: they are not best thought of as identifying attitudes or feelings of individuals. Rather, they identify patterns of behavior, frameworks that determine meaning, and systematic consequences of an individual’s actions. The accusation of (to just choose a single, over-simplified example) racism isn’t an accusation that you intend harm or harbor ill will toward people of another race.1 Instead, it is the accusation that what you’ve done or said perpetuates, reinforces, or endorses a system that unjustly distributes burdens and benefits (here, by race).

To understand what is at stake in distinction between institutional structures and individual attitudes, it will be helpful to consider a few examples.

- Case 1 In the stereotypical account of racism, we have someone like Tom Metzger, who has long advocated for a particularly violent form of white racism. This is a case where the individual attitudes match the institutional structures.

- Case 2 In addition, there are cases in which there are hostile attitudes toward groups of individuals based on false and morally irrelevant features that are nonetheless not forms of structural violence. Suppose, say, that I believed that people with webbed toes are likely to be untrustworthy. As a result, I don’t befriend people I know have webbed toes, I don’t hire them, and I don’t vote for them when they run for public office. Clearly, I’m a bad person for holding these views and behaving in this way—I should not behave in this way. This is not, however, an instance of structural violence because there is no social institution that creates asymmetrical rewards and burdens based on morally arbitrary categories. To put it a bit bluntly: in this case, I’m a jerk, but I’m a jerk on my own. In contrast, someone like Tom Metzger is a jerk, but he is empowered by institutions that extend far beyond him.

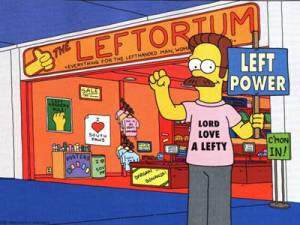

- Case 3 As a final case: consider the plight of left handed people. A large portion of our artifacts are designed to be used by people who primarily use their right hand: the desks in a college lecture hall, the trackball sitting next to my computer, and more. There are patterns of behavior—institutionalized practices—that impose burdens on left handed people. I don’t think, though, that right handed people have ill-will toward or actively dislike lefties (at least, in virtue of their left-handedness). Nonetheless, the history and practices do have an effect.

Given these cases, we can begin to see how the differences between structural violence and individual attitudes come apart—and how, if we only understand, e.g., racism in terms of the kind of explicitly endorsed ill-will of Metzger or Stormfront, we will fail to grasp how truly insidious and pervasive the phenomena are.2

Before moving on, I do want add the following: none of this is to deny the reality that there are oppressors and that oppression is a fundamental problem. To take our basic case: racism is a deep problem, and it is not one that can be overcome by occasionally recognizing that non-White people exist, are deserving of respect, are persons, and the like. However, the phenomena I’m interested in lie in the vast domain that is bounded by Cases 1 & 2. That is, I gather we all agree that people of the sort who appear in Case 1 are really problematic, and I think we’d agree that the sort of people who appear in Case 2 are likely quirky and harmless. (If not, I’ve chosen a bad example.)

There is clearly more to racism than just Case 1 types who actively endorse and seek out enforcement of racist institutions. Sometimes the accusation of racism is one that targets endorsers, and sometimes it targets people who merely benefit from or reinforce these institutions. Sometimes this takes the form of the casual racism (e.g., alluding to people of other races by slurs when among friends of the same race); sometimes it takes more sophisticated forms (e.g., the endless attempts by white guys to provide “scientific evidence” of their superiority); and sometimes it takes the form of high minded ideals like “urban renewal” and “reducing crime.” These are all instances of racism.

Wait, is there no difference between well-meaning white folks and Stormfront?

Of course, there is some difference between the person who intends harm to others and the person who incidentally causes it. However, this isn’t a difference in the moral quality of the act, as the act still has the consequences that it has regardless of the intention of the agent. Whether you meant well or ill is probably of little consequence to someone who is left to deal with the real consequences of your action.

The difference that intentions might make here is in how we ought to regard the agent who brought about the act: are they deserving of moral reproach and sanction or a more sympathetic correction? The person who meant the harm he brought about is deserving of moral reproach and sanction, but someone who unintentionally did so might be deserving of more education than condemnation.

As a result, accusations of racism (et. al.) need not be construed as “characterological,” as indicating a defective “soul” or a cruel attitude. These accusations instead highlight the role a person is playing in a system of domination and oppression. The criticism is about the harms one perpetrates and the unjust benefits one receives from participating in such a system.

Again, none of the foregoing should be construed as lessening the sting of accusations of racism or absolving those who have behaved in ways that are racist from blame. Indeed, at best it suggests that “inadvertent racists” might be due something other than condemnation; it does not require that they are. The point of this analysis is that it reconfigures the obligations of people who are anti-racist. People who want to fight racism don’t only (or even primarily, perhaps) need to change themselves—they need to change the institutions all around them. It likely is impossible for us to escape racism at the moment, but it isn’t impossible for us to critique those institutions, be aware of our complicity in them, and change them so that they match our aspirations toward justice.

Why there is no such thing as “reverse” racism

People who make claims suggesting that there is a phenomenon of “reverse” racism are making a basic mistake: they are conflating intentions with institutions. To take our overly-simplistic racism example: it isn’t possible for African Americans to be racist against whites in the US, as the institutions that give order and meaning to our lives don’t disadvantage whites.3 However, it is possible for African Americans to be racist against other African Americans as well as other NBPoC, and it surely is possible for African Americans to harbor hostility and intolerance toward white people.

Clearly we need get clear on some distinctions in order to better account for the phenomena. If racism is possible only within an institution and is not as such marker of intentional hostility, we do need to be able to mark off people who are hostile. To that end, we might use terms like “bigotry” (i.e., obstinately holding intolerant beliefs) and “prejudice” (i.e., an unreasoned hostility or antagonism). Oppressed people surely can have intolerant and unreasoned antagonism about people who benefit from systems of oppression, even if they cannot oppress those people. As a result, “reverse racism” isn’t a thing so much as it is a category mistake.

- The example is over-simplified because it implicitly understands “race” in terms of the “Black/White” continuum. There are many other races, and framing debates about racism solely in terms of the Black/White continuum distorts our analysis of racism and further erases these other races from our discourse (and thus reinforces a kind of racism against NBPoC). In addition, I should add that I’m considering racism an example of the broader phenomenon of structural violence, and so we could write a quite similar article about “sexism,” “heterosexism,” “classism,” “cissexism,” and the like. ↩

- Figuring out just how deep the problems go is the project of my “Moral Dimensions” course. There, we explore how these institutions become deeply ingrained habits that have profound effects on our psychology and embodiment. ↩

- At least, insofar as they are white. As I noted in the earlier post on institutional critiques, our political identities are “intersectional,” and so one’s being a woman, gay, trans, or poor might put them in a disadvantaged position. ↩