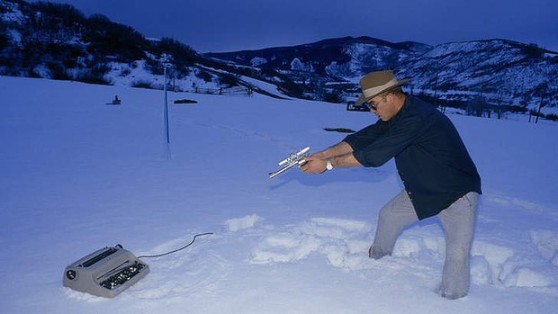

Clearly, this man should never be allowed to get near a university.

It is now possible to have a really bad, no good, terrible day that the whole world can witness and that you can never take back. I tell my students that I’m eternally grateful that I was able to be young prior to the proliferation of digital cameras and the development of the world wide web because my youthful indiscretions aren’t preserved for posterity. Even beyond the hormone-fuelled irrationality of youth, I’ve surely been a jerk and fired off inappropriate emails (or ruined more than my share of dinner conversations) even after receiving my PhD.1 Digital communication platforms not only enable us to give in to snap judgements and jerkish responses, some reward and encourage it. It is really easy to be flip in 140 characters, and it is extraordinarily difficult to be deep or insightful within the constraints of Twitter. Whatever we make of the Steven Salaita case case itself, it seems to me that this issue is something we, the scholarly community, need to think through and come to some sort of consensus on because it is only going to loom larger as younger scholars who grew up with social media enter academia.

I want to suggest that there are two problems facing academia: first, the regulative ideal of scholarly behavior arose at a time when it was substantially more difficult to engage in the sort of bad behavior that various information technology platforms enable and enourage. Second, there is a culture clash between scholarly endeavours and information technology practices; whereas the former is (or aspires to be) permanent, considered, careful, and thoughtful, the latter includes uses that are way more ephemeral, instantaneous, off-the-cuff, and “uncareful” (precisely because it can be corrected or updated for little to no cost).

Scholars, the passions, and the “post” button

Although it has been a long time a-comin’, academia is running headlong into a bit of a crisis: what are the norms of propriety for public behavior by faculty—and what counts as “public” behavior? The recent Salaita raises these issues (among many others!) with regard to online personae or performances. While there is much to say about that case, I will reserve what little I feel that I have to say about it directly for the appendix, below. (Spoiler alert: UIUC blew it badly in almost every way it could.) My interest here is institutional in nature: in the clash or mismatch between institutional norms and the extent to which one’s job as a scholar dictates one’s actions outside of the academy. In my next post, I will address issues surrounding these sorts of public performances and the classroom.

A portrait of the scholar as someone with normal impulse issues

Ah, the life of the scholar and gentleperson: endless hours of unstructured time to perform research near to one’s heart, ample and constructive feedback from peer reviewers, occasional but rewarding interactions with students who are keen to learn, deep engagement with colleagues who value the life of the mind and your work, tweed coats with leather elbow patches, summers off to recharge and refocus, guaranteed employment for life, and a lifetime spent having careful, precise, well-researched,, and respectful discussions with one’s peers. In the words of Pepper Brooks: “That’s rad.”

Of course, it isn’t like that anymore for most faculty.1 Most faculty aren’t even in full-time or tenure track positions, so they are in a position of spending their lifetime applying for jobs. The endless hours of unstructured time for scholarly endeavours is filled with teaching, administrative, committee, and other obligations. The ever more demanding standards for hiring, promotion, and tenure means that summers are periods of frenetic efforts to crank out articles that will by-and-large go unread—sometimes even by the peer reviewers themselves. Sometimes this writing is accompanied by summer school teaching that provides a necessary income supplement for junior faculty with the student loan debt of someone with an advanced degree who is paid entry-level wages.

Another difference between the idyllic conception of the scholarly life and the realities of academia comes from the transformation of the public sphere caused by the proliferation of electronic publishing technologies. We ought to recognize that the norms of scholarly endeavors arose at a time when it was rather more difficult to make one’s ill-informed, prejudiced, offensive, obnoxious, etc. views widespread. The mythos of the scholar as gentleperson is built in part on the fact that the opportunities for scholars to have public meltdowns were relatively few and infrequent.

In earlier generations, it took a great deal of effort and expense to get ideas out there—even if you had access to a spirit duplicator (you know, a “ditto” machine, the device that made purple copies with the aroma of information and solvent), for example, you still had to carefully produce an error-free original by hand, run the machine, and then find a way to distribute the material. Nowadays, though, one can globally publish whatever one wants instantaneously at little or no cost. If you make an error, it is simple, quick, and inexpensive to fix. Search engines help bring folk to your work, which obviates the need to put one’s manifestos on the windshields of parked cars or distribute them while standing in front of the local grocery store.

All of this time, effort, and infrastructure slows down the publication process, and so the norms of public behavior for scholars were built around the fact that . . . well, you had to put a lot of work into making a spectacle of one’s quirkier or ill-considered beliefs. Nowadays, though, scholars may use university-provided technology to fire off a missive to the entire campus instantaneously and at zero cost. Scholars can use those same resources to take less than a minute to sign up for social media or online publishing platforms that allow authors to reach billions of people who have access to networked computing devices—instantly and for free. Really, they let just anyone have a website these days. Indeed, it is likely—almost certain—that the readership of a scholar’s social media or other online publishing far exceeds the readership of that person’s scholarly publications.

Once we add microblogging social networks like Twitter, the problem only get worse. In those contexts, one doesn’t reply to detractors by studying the context of the detractor’s tweet, gathering evidence, sourcing one’s claims, and then—perhaps months later—responding with a carefully worded, well-referenced assessment of the original tweet. The platform itself is really suited to quick bursts of commentary: tweets are limited to 140 characters, people follow large number of other twitter users (resulting in a veritable flood of tweets), and the norms of the discourse lean to the immediate and ephemeral rather than the scholarly and archival. It is quite a bit more like having a conversation with lots of people (many of whom you might not know) in a public place than it is participating in an academic publishing endeavor. And when I say “lots” I don’t mean “many for an academic venue”—I mean on the order of tens of thousands or tens of millions.

So?

Among the issues raised by the Salaita case is the following: how ought we to regard the “informal” online publishing of faculty? Faculty use social media and blog about matters that interest them; some of these interests are scholarly, some professional, some political, and some are just, you know, interests—things people occupy themselves with when not, you know, working. What is the relationship between the professional duties and standards of academics and their participation in various online fora? In a previous post, I discussed this issue from the perspective of what might be good for academic philosophy as a discipline. Here, I want to pursue this the other way ’round: how are we to treat the online personae, performances, and publishing of faculty?

I guess the big question I have is this: should departments not hire candidates who have said intemperate or offensive things on the internet? I suspect that people want to give a formal answer—that is, some principle that gives us a decision procedure independent of the content and context of the intemperate or offensive utterances—but I tend to be skeptical of that approach to these matters.

An analogy: kids these days

Indulge me for a moment as I start by talking about something that may not be obviously connected to the issue at hand. I happen to really like young people. Really, one of the great rewards of being a faculty member is getting to work with people who are full of energy, are trying to figure it all out, and who haven’t seen it all. Of course, youthful exuberance comes with a lack of wisdom and, to be candid, more than a bit of a problem with impulse control. Kids make mistakes in their explorations of life. That’s part of growing up, or so I like to tell myself when I suffer an intrusive memory of events that I’ve paid good money for alcohol and drugs in order to forget.

I made many mistakes myself. Were there a god, I would thank that god every day for allowing me to grow up prior to the invention and proliferation of digital cameras and social media. To get a sense as to why, consider this: hormone addled teenagers now have the ability to take pictures of themselves (by which I mean their junk) and others and broadcast them around the globe instantaneously. That is to say: current technologies allow kids to not only act out, but to do so in a way that leaves what may be an instantaneous, international, and permanent record. When I screwed up, maybe 20 people would see it and another 40 might hear a rumor about it over time. When kids these days screw up, the unambiguous evidence of their poor judgment is on display to people all over the globe.

Being a kid has changed, and I suspect that, as time goes on, we’ll be less concerned about the poor judgment kids exercised on social media. We may cringe at some of the material, but of course we do that now about, say, the fashion sense of at least some folks in the 1970s or 1980s or photographs of ourselves geeking out at a concert for a band that we come to realize now was pretty crappy.2 More importantly: even if I might have, say, a Polaroid of you trying to snort a mountain of blow off the bar at Studio 54, I’m probably not going to include a scan of that in my contribution to your festschrift. Those kinds of photos nowadays live on servers from the moment they are taken, and even “secure” servers are subject to hacking. . . .

Scholars and trolls?

There is a great deal of similarity between the case of “kids these days” and the case of academics. It is entirely unreasonable and unfair to expect humans not to lose their shit. As we increase the amount of time we spend publishing in the instantaneous, mass-media online, we increase the likelihood that we might have one of our “not my best moment” moments in a spectacularly public way.

Nobody, I hope, thinks that my snap judgment about the character of the person who cuts me off in traffic and subsequent utterances about the easy virtue and animal-like appearance of that person’s constitute anything like a professional judgment—even if I’m a traffic ethicist. (I’m not.) Participating in an online flame war—especially on Twitter—is rather more like road rage than it is a sign of a scholarly failure.

Of course, not everyone who is active on Twitter ends up being a jerk, and maybe being a jerk on twitter reflects one’s failure at being active on Twitter. I’m open to that possibility, but, just between us, I think it is just a load of bollocks. But let’s grant that one way to be bad at being active on Twitter—or any online medium—is giving in to the impulse to throttle people who clearly deserve throttling. However, being bad at being active on Twitter isn’t a sign that one is a poor scholar, a defective teacher, or a bad colleague. Hiring practices at universities ought to reflect one’s worthiness as a professional.

A parting, perhaps enigmatic, thought

As I intend to discuss in a later blog post, not every context is a seminar room—and, actually, the “seminar room” isn’t as safe a space for inquiry as some like to think. But the scholarly attitude I might take with my students and colleagues in a seminar room isn’t necessarily appropriate for other contexts (e.g., political protests, attending a comedy show, or giving a eulogy). I mean, sure, you could venture into your local fight club wanting to talk through the club’s sublimation of intimacy through violence rather than fight. Given the requirement that one fight during a first visit to a fight club, though, I suggest that you put up your dukes rather than yammer on about Butlerian deconstruction of the very idea of gender.

Next time: An action packed investigation into the idea that students who know that their professors are jerks with views about politics should fear for their educations. For once, someone will think about the children!

Appendix: some thoughts about the Salaita case

I’m not interested in discussing the Salaita case per se, for quite a few reasons. Among those reasons is that UIUC’s choice to dehire Salaita was straightforwardly reprehensible for procedural (or at least formal) reasons alone. UIUC’s expectation—indeed, I’d venture to say the expectation of anyone who works in academia—was that Salaita would resign from his position shortly after accepting the offer, relocate from Virginia to Illinois, and be ready to begin teaching at the start of the Fall 2014 semester on August 24. Whatever its flaws, the process of academic employment requires a significant amount of good will in order to work; faculty resign once the offer is extended so that the department that they are leaving can make the arrangements that they need to, and, since changing jobs in academia frequently involves long-distance moves, so that they may relocate in a timely manner.

The move by UIUC undercuts the good will that allows the practice to succeed. If universities want to be able to have full reviews at the Board of Trustee (BoT) level shortly before the academic year begins, then faculty will have to avail themselves of at least one of the two following options: (i) faculty won’t resign their positions until after the final contract is approved by the BoT or (ii) faculty will demand a “pay or play” clause in their contract. I’m not an administrator, but I wouldn’t want to have dedicate resources to finding coverage for classes that are being taught by faculty who resign a week before the semester begins, and I surely wouldn’t want to pay someone a lump sum not to work for me. (Administrators who are comfortable with the latter, please contact me. My rates for not teaching at your institution are surprisingly reasonable.) The current system may not be wonderful, but the consequences of breaking it are going to be pretty bad for academia.

Naturally, there is much to say about Salaita’s case: the potential encroachment on academic freedom, the problematic influence of donors on academic policy, the complete and utter meltdown of Cary Nelson, the role of Zioinism in shutting down reasoned discourse, and so on. Others have discussed these issues in a more timely and insightful manner. Plus, I’m not interested in turning this site into “One Jew’s Exploration of Every Aspect of the Israel/Palestine Situation.” If you’re interested in that case, you could do worse than check out the coverage by Corey Robin.

- I am happy to leave aside the question of whether it ever was really like that as well as the question as to whether we’re better off now than we were—or would have been—then. ↩ ↩

- Not me, of course. My mistakes weren’t fashion or music, as I have always had exceptional taste. But I have ruined more than my fair share of dinner party conversations, and I am grateful that those conversations are lost to the mists of time rather than stored on server farms somewhere. ↩